Epidermis (skin)

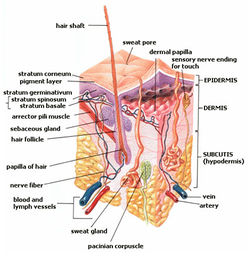

The epidermis is the outer layer of the skin,[1], a stratified squamous epithelium,[2] composed of proliferating basal and differentiated suprabasal keratinocytes. The epidermis acts as the body's major barrier against an inhospitable environment.[3] In human, it is thinnest on the eyelids at .10 mm (0.0039 in) and thickest on the palms and soles at 1.5 mm (0.059 in).[4] It is ectodermal in origin.

Contents |

Structure

Cellular components

The epidermis is avascular, nourished by diffusion from the dermis, and contains keratinocytes, melanocytes, Langerhans cells, Merkel cells[1], and inflammatory cells. Keratinocytes are the major constituent, constituting 95% of the epidermis.[2] Rete ridges are epidermal thickenings that extend downward between dermal papillae.[5]

Layers

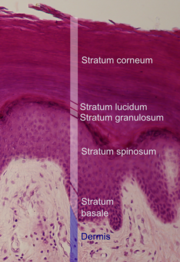

The epidermis is composed of 4-5 layers depending on the region of skin being considered. Those layers in descending order are the cornified layer (stratum corneum), clear/translucent layer (stratum lucidum), granular layer (stratum granulosum), spinous layer (stratum spinosum), and basal/germinal layer (stratum basale/germinativum).[3] The term Malpighian layer (stratum malpighi) is usuallly defined as both the basal and spinosum layers as a unit.[2]

Cellular kinetics

The stratified squamous epithelium is maintained by cell division within the basal layer. Differentiating cells delaminate from the basement membrane and are displaced outwards through the epidermal layers. In the stratum corneum the cells lose their nucleus and fuse to squamous sheets, which are eventually shed from the surface (desquamation). In normal skin, the rate of production equals the rate of loss,[2] taking about two weeks for a cell to journey from the basal cell layer to the top of the granular cell layer, and an additional four weeks to cross the stratum corneum.[3] The entire epidermis is replaced by new cell growth over a period of about 48 days.[6]

Organogenesis

Epidermal organogenesis, the formation of the epidermis, begins in the cells covering the embryo after neurulation, the formation of the central nervous system. In most vertebrates, this original one-layered structure quickly transforms into a two-layered tissue; a temporary outer layer, the periderm, which is disposed once the inner basal layer or stratum germinativum has formed. [7]

This inner layer is a germinal epithelium that give rise to all epidermal cells. It divides to form the outer spinous layer (stratum spinosum). The cells of these two layers, together called the Malpighian layer(s) after Marcello Malpighi, divide to form the superficial granular layer (Stratum granulosum) of the epidermis. [7]

The cells in the granular layer do not divide, but instead form skin cells called keratinocytes from the granules of keratin. These skin cells finally migrate to form the cornified layer (stratum corneum), the outermost epidermal layer, where the cells become flattened sacks with their nuclei located at one end of the cell. After birth these outermost cells are replaced by new cells from the granular layer and throughout life they are shed at a rate of 1.5 g (0.053 oz) per day. [7]

Epidermal development is a product of several growth factors, two of which are:[7]

- Transforming growth factor Alpha (TGFα) is an autocrine growth factor by which basal cells stimulate their own division.

- Keratinocyte growth factor (KGF or FGF7) is a paracrine growth factor produced by the underlying dermal fibroblasts in which the proliferation of basal cells is regulated.

Skin color

The amount and distribution of melanin pigment in the epidermis is the main reason for variation in skin color in modern Homo sapiens. Melanin is found in the small melanosomes, particles formed in melanocytes from where they are transferred to the surrounding keratinocytes. The size, number, and arrangement of the melansomes varies between racial groups, but while the number of melanocytes can vary between different body regions, their numbers remain the same in individual body regions in all human beings. In white and oriental skin the melansomes are packed in "aggregates", but in black skin they are larger and distributed more evenly. The number of melansomes in the keratinocytes increases with UV radiation exposure, whilst their distribution remain largely unaffected. [8]

Additional images

|

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005) Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (10th ed.). Saunders. Page 2-3. ISBN 0721629210.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 McGrath, J.A.; Eady, R.A.; Pope, F.M. (2004). Rook's Textbook of Dermatology (7th ed.). Blackwell Publishing. pp. 3.1–3.6. ISBN 9780632064298.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Marks, James G; Miller, Jeffery (2006). Lookingbill and Marks' Principles of Dermatology (4th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 1–7. ISBN 1-4160-3185-5.

- ↑ Brannon, Heather (2007). "Dermatology - Epidermis". About.com. http://dermatology.about.com/cs/skinanatomy/g/epidermis.htm.

- ↑ TheFreeDictionary > rete ridge Citing: The American Heritage® Medical Dictionary Copyright 2007, 2004

- ↑ Iizuka, Hajime (1994). "Epidermal turnover time". Journal of Dermatological Science 8 (3): 215–217. doi:10.1016/0923-1811(94)90057-4. PMID 7865480.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Gilbert, Scott F (2003). "The Epidermis and the Origin of Cutaneous Structures". Developmental Biology. Sinauer Associates. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=dbio&part=A2929.

- ↑ Montagna, William; Prota, Giuseppe; Kenney, John A. (1993). Black skin: structure and function. Gulf Professional Publishing. p. 69. ISBN 012505260X. http://books.google.com/?id=BpL8V2YJkQ4C&pg=PA69.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||